Seção Livre

BABEL, Alagoinhas - BA, 2024, v. 14: e18668.

CARVALHO, Vera Lucia Lima. Discussing three frameworks of reflection in language teacher education Babel: Revista Eletrônica de Línguas e Literaturas Estrangeiras, 2024, v. 14, e18668.

Discussing three frameworks of reflection in language teacher education

Discutindo três plataformas de reflexão em educação de professores de Línguas

Vera Lucia Lima Carvalho

Abstract: The present article discusses three different frameworks of Reflective Practice (RP) intended to foster reflection in the fields of English Language Teaching (ELT) and Language Teacher Education (LTE). Therefore, we look at structural platforms of procedures or ways of engaging in reflection and/or analysing its outcomes. The following are the frameworks, discussed in terms of their contribution for the refinement of both individual and collaborative professional development: Zwozdiak-Myers’s framework of reflective practice, Farrell’s Framework for reflecting on practice and Edge’s framework of cooperative development. We look into the term critical in the field of LTE and discuss the frameworks after a brief overview of the complexities involved in reflection, ranging from daily classroom procedures, to hegemonic assumptions and personal philosophical stances, including assumptions and beliefs. In a very generalised way, it can be said that the first two frameworks are designed to guide and structure evidence of reflection in self-study, whereas the third one takes a more collaborative approach, although the three frameworks can be complementary and may have practical overlaps of application.

Keywords: Language Teacher Education. Reflective Practice. Frameworks.

Resumo: O presente artigo discute três diferentes plataformas estruturais de Prática Reflexiva, destinadas a incentivar a reflexão na área do ensino de Língua Inglesa e de educação de professores de línguas. Portanto, analisamos plataformas estruturais de procedimentos ou maneiras de engajamento em reflexão e/ou análise dos seus resultados. As seguintes são as plataformas, discutidas em termos de sua contribuição para o refinamento de ambos os desenvolvimentos, individual e colaborativo: o Modelo de Zwozdiak-Myers para Prática Reflexiva, o modelo de Farrell para refletir sobre prática e o modelo de Edge de desenvolvimento cooperativo. Analisamos o termo “crítico” na área de educação de professores de línguas e discutimos as plataformas, depois de uma breve passagem sobre as complexidades envolvidas em reflexão, que vão de procedimentos do dia-a-dia em sala de aula, a considerações e posicionamentos hegemônicos e filosóficos, incluindo pressupostos e crenças. De forma generalizada, pode-se dizer que as duas primeiras plataformas são construídas para guiar e estruturar evidência de reflexão em auto estudo, enquanto que a terceira toma uma abordagem mais colaborativa, embora as três possam ser complementares e possam ter pontos de aplicação em comum.

Palavras-chave: Educação de professores de línguas. Prática Reflexiva. Plataformas.

Introduction

Practices intended to foster reflection in the fields of English Language Teaching (ELT) and Language Teacher Education (LTE) have become close to mandatory, despite criticisms faced by Reflective Practice (RP) (Farrell, 2012; Schön, 1983), associated with matters of definition, interpretation, content and forms of application, which may overlap with ideological and political perspectives (Eraut, 2002). Such discussions are not the centre of our concern here, although they are interconnected with the focus of our interest. Especially considering the aspects of contents for reflection and forms of application of activities for reflection, the present article discusses three different frameworks which embrace RP’s value and contribution for the refinement of both individual and collaborative professional development:

• Zwozdiak-Myers’s framework of reflective practice (2012);

• Farrell’s Framework for reflecting on practice (2015);

• Edge’s framework of cooperative development (Edge, 1992; 2002; Edge; Attia, 2014).

The term “RP framework” in the present discussion refers to a structural platform of procedures or ways of engaging in RP and/or analysing its outcomes. The frameworks discussed can be used in combination, or chosen on the basis of their flexibility to accommodate different levels of experience (from novice to more experienced educators) and incorporate both individualised and collaborative forms of RP, bringing along ideas that can illuminate the understanding of educators’ reflection as individuals or as a community (Lave; Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). Before presenting and discussing the frameworks, I must make it clear what is meant by “critical reflection” and I also invite the reader to a brief overview of discussions related to typologies, content and levels of reflection.

Critical reflection in Language Teacher Education

The term “critical” within LTE, especially in the “outer circle” (Kachru, 1985), is certainly most immediately associated with polemic socio-political debates, such as the notion of English as a global language (Crystal, 1997, 2003, 2012), English as an international language (Holliday, 2005) and linguistic imperialism (Canagarajah, 1999; Pennycook, 2015; Phillipson, 2009). However, in association to such debates, complexities for both teachers and teacher educators can vary in nature, ranging from decisions about daily classroom procedures, or relational matters (with students, colleagues and administrators) to hegemonic assumptions and personal philosophical stances, including assumptions and beliefs. Critical consciousness, which Freire (2014) would call “conscientization”, relates to being aware of a complex and wide range of professional aspects, including the questioning of assumptions and practices in relation to cultural and political stances. This is linked to the notion of personal assumptions, in the following way:

The most distinctive feature of the reflective process is its focus on hunting assumptions (…) in many ways, we are our assumptions. Assumptions give meaning and purpose to who we are and what we do. Becoming aware of the implicit assumptions that frame who we think and how we act is one of the most challenging intellectual puzzles we face in our lives. It is also something we intrinsically resist, for fear of what we might discover (Brookfield, 1995, p. 2).

Brookfield distinguishes assumptions into three broad categories: paradigmatic, prescriptive and causal, considering the first to be the hardest to uncover. He defines paradigmatic assumptions as “the basic structuring axioms we use to order the world into fundamental categories” (Brookfield, 1995, p. 2). This means that we do not even realise they are our own particular assumptions, as we consider them to be “the truth”, perhaps better defined as “objectively valid renderings of reality” (ibid). Examples would be taking for granted that “adults are self-directed learners” (ibid), or that “good educational processes are inherently democratic” (ibid). He goes on to describe prescriptive assumptions as extensions of (because they are grounded on) our paradigmatic assumptions. Prescriptive assumptions are concerned with “what we think ought to be happening in a particular situation” (ibid. p. 3) and so, they derive from our examinations of how we think teachers should act, students should act, environments and practices should be etc. Causal assumptions are described as the easiest to uncover. These are related to “the conditions under which processes can be changed” (ibid. p. 3). Brookfield explains that this is usually stated in predictive terms. Thus, teachers have assumptions such as, if work is done this way, then such and such is the outcome. For example, “if we make mistakes in front of the students, this creates a trustful environment for learning, in which students feel free to make errors with no fear of censure or embarrassment” (ibid). Brookfield considers the discovery and the investigation of causal assumptions as the start of the reflective process, and teachers must then find a way to uncover the more deeply embedded assumptions.

The division above (the categories of assumptions) is in agreement with what other authors consider in relation to critical reflection within teacher education. There is a common concern with integrating other dimensions for preparing second language teachers and their educators that go beyond learning knowledge and skills. For example, Day (1999) considers as “development” those learning experiences that contribute to the quality of education, highlighting the moral purposes of teaching throughout their teaching lives. Similarly, Freeman (2004) argued that critically reflecting “is also about becoming educators who contribute deliberately and critically to the discourses and practices that constitute schools and society” (p. 191). Eraut (1994), who also constructed some criticisms of RP, acknowledges that professionals should demonstrate moral commitment to students’ well-being and progress. Reappraisal of experience and assumptions is highlighted by Farr (2015), who favours “reappraising old assumptions in the light of new information” (p. 67).

Moreover, Brookfield (1995) highlights his concern with the absence of a critically reflective stance toward what we do. Without it, we blame ourselves for whatever goes wrong in our practice and in our students’ learning process, falling into “demoralization and self-laceration” (p. 2). He explains what happens when the reflective habit is absent:

We take action on the basis of assumptions that are not unexamined and we believe unquestioningly that others are reading into our actions the meanings that we intend. We fall into the habits of justifying what we do by reference to unchecked “common sense” and of thinking that the unconfirmed evidence of our own eyes is always accurate and valid. “Of course, we know what’s going on in our classrooms”, we say to ourselves. “After all we’ve been doing this for years, haven’t we?” Yet unexamined common sense is a notoriously unreliable guide to action (Brookfield 1995, p. 4).

Iconic consciousness occurs when an aesthetically shaped materiality signifies social value. Contact with this aesthetic surface, whether by sight, smell, taste, touch provides a sensual experience that transmits meaning. The iconic is about experience, not communication. To be iconically conscious is to understand without knowing, or at least without knowing that one knows. It is to understand by feeling, by contact, by the evidence of the senses' rather than the mind (2008, p. 782).

What can be concluded from this section is that critical reflection must interrelate with practice in education, so that RP conforms to ethics, commitment to self-understanding and willingness to engage in this endeavour. The next section looks at the way in which researchers classify reflections into typologies of reflection, according to the different sorts of issues upon which teachers and/or their educators may reflect when pursuing improvement of their practice.

Typologies, content and levels of reflection

Perhaps because “The potential matters for reflection are limitless” (Jay; Johnson, 2002, p. 75), classifications, categorisations and distinctions have been made related to types of reflection, types of decisions to be made and the content related to these. Moreover, the nature of issues normally included in RP programmes has undergone changes along the development of LTE, with pertinent observations, such as Freeman’s (1982) distinction between the terms “training” and “development”, which, in broad terms, would represent a correlation with behaviouristic and more constructivist philosophies of education. The author relates this distinction to what sorts of issues teachers can possibly reflect upon: training relates to teaching skills, for example, how to sequence a lesson or teach a dialogue. Development focuses on “the process of reflection, examination, and change which can lead to doing a better job and to personal and professional growth” (p. 21).

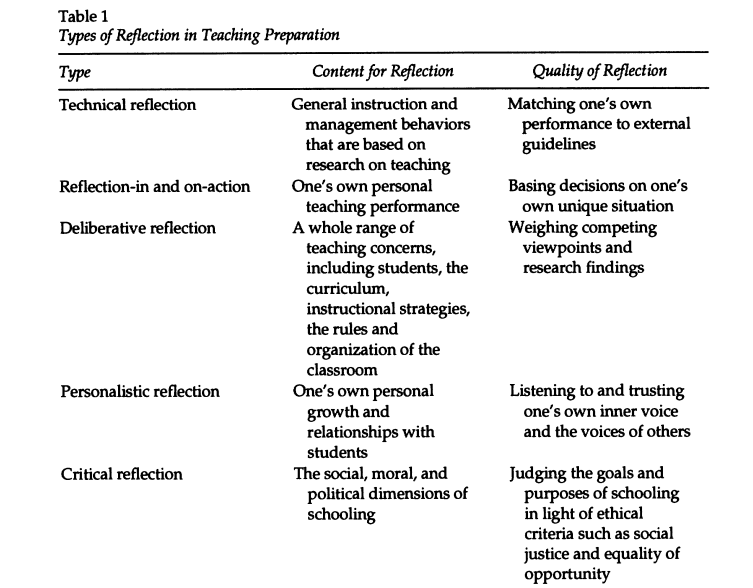

The above resonates with Dewey’s (1933) contrast between reflective and routine action, which also relates to Van Manen’s (1977) classification (which is based on Aristotle’s concepts of episteme and phronesis) of technical rationality (the daily practical thinking of teachers while planning and developing their practice) and critical rationality (moral and ethical questions, including cultural, social, and political contexts). In turn, this has also influenced Valli’s (1992; 1997) “types of reflection” (technical reflection, reflection-in and on-action (Schön, 1983), deliberative reflection, personalistic reflection, and critical reflection). Valli (1992) provides a relation of the contents linked to each type of reflection, illustrated in the table below:

Table 1: Valli’s Types of Reflection in Teaching Preparation (Valli, 1992, p. 75)

Although Valli creates space for the personal dimension of reflection (named as personalistic reflection), the content related to it is vague and limited (“one’s own personal growth”). Moreover, as clearly seen from the table, the social, moral and political dimensions are depicted as content for reflection, belonging to a separate type of reflection, with no indication of overlaps or correlation with the other contents. This reminds us of how difficult it is to define typologies of reflection in a way that can accommodate complexities and overlaps.

The fact remains that there will always be “a number of persistent concerns in the professional practices of teachers” (Hedge, 2001, p. 1). Some examples of these concerns (below) reveal that in their processes as decision-makers, in managing classroom processes and educational settings, teachers make use of a complex combination of professional skills and reasoning that include different levels of reflection, independently of their length of professional experience:

What do I set up as aims for my next lesson with this class and what kind of activities will help to achieve those aims? How do I balance its content in relation to what I see of my students’ needs for English in the world outside the classroom and in relation to the examinations for which we are preparing? How do I deal with this reading text in class? What amount of out-of-class work can I reasonably expect my learners to do? How do I make best use of a textbook I am not entirely happy with? How can I motivate my learners to be more active? What are my ultimate goals with this class? And can I usefully discuss and negotiate any of these things with my learners? (Edge, 2001, p. 1)

Edge (2001) acknowledges the fast development of the knowledge base for effective practice derived from research in “education, applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, pragmatics, cultural studies, second language acquisition studies, curriculum studies, psychology, to name but a few” (p. 1). Such development also influences what teachers possibly reflect on.

As for the depth of this myriad of professional concerns, various authors suggest (or agree with) a correlation between level of experience and the direction and depth of reflections, or a correlation between assumptions and justifications for action. These include Brookfield (1995, 2015), King and Kitchener (1994), Moon (1999, 2013), Tsui (2003), Calderhead and Gates (2004), Zwozdiak-Myers (2012) and Magolda and King (2008). In summary, these works suggest the progressive development of reflective capacity and trace stages of epistemological cognition. In general terms, this would mean that “the capacity to reflect is developmental and progressive in nature, from working with certain basic, concrete knowledge to working with provisional or uncertain knowledge” (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 21).

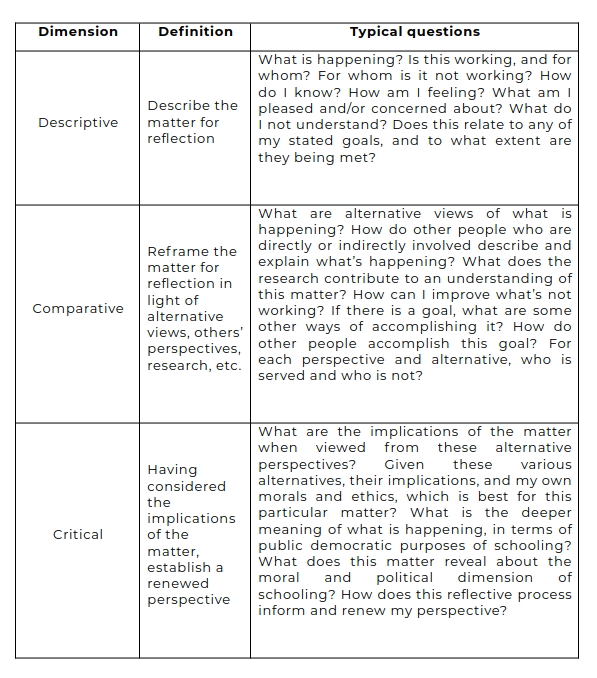

Jay and Johnson (2002) approach the content upon which teachers reflect in terms of questions, which are framed into three dimensions (descriptive, comparative, and critical), as represented on the table below:

Table 2: Jay and Johnson’s Typology of Reflection: dimensions and guiding questions (2002, p.77)

The description of Jay and Johnson’s (2002) dimensions of reflection are summarised as follows: descriptive reflection, in written or spoken narrative, involves determining the matter for reflection and decisions to be made, the end and the means to achieve it, noting the salient features of a situation. This resonates with Schön’s ideas, as “professional practice has at least as much to do with finding the problem as with solving the problem found” (1983, p. 18). Comparative reflection involves the understanding of others’ points of view, or other possible solutions. Therefore, “different interpretations of the same matter are compared” (Jay; Johnson, 2002, p. 78). The authors understand that comparative reflection expands and enriches understanding. However, the third dimension of reflection, the critical reflection, is what Schön (1983) describes as “a way of integrating, or choosing among, the values at stake in the situation” (p. 63). Analysing multiple perspectives often involves making a judgment. In this case, the consideration of what is “best” has to be pondered in relation to the social and political context: “Perhaps what we have formerly considered best practice may not meet the needs of a student; what’s natural in one culture may be inappropriate for another” (p. 79). In a sense, the three dimensions represent a widening of the lens, from the situation at hand to multiple perspectives on a situation to an appreciation of the bigger picture of implications surrounding the problem at hand.

Farrell (2015) considers that there is agreement on three basic different levels of reflection: “descriptive (focussing on teacher’s skills), conceptual (the rationale for practice) and critical (examination of socio-political and moral and ethical results of practice” (p.9). His framework for RP considers all levels and the possibility of overlaps. This could possibly be related to studies on teachers’ professional life cycle, however, considering that expertise is a complex issue inside the universe of experience, Brookfield (1995) reminds us that “longevity of service is not in itself a guarantee of critical reflection” (p. xiv). This is echoed by Tsui (2003), who notes that “expertise in teaching is a continuous and dynamic process in which knowledge and competence develop in previous stages and form the basis for further development. Therefore, the dimensions of reflection by Jay and Johnson (2002) are an idea endorsed by Farrell (2015):

There is agreement on three basic different levels of reflection (although some may use different terminology to explain them) that teachers can work from (e.g., Farrell, 2004, 2007a; Jay and Johnson, 2002; Larrivee, 2008; Van Manen, 1977). These three levels are called: descriptive (focus on teacher skills), conceptual (the rationale for practice) and critical (examination of socio-political and moral and ethical results of practice—see critical pedagogy above) (Farrell, 2015, p. 9).

A variety of strategies, procedures and tools have been developed to help teachers and teacher educators to examine and reflect upon their professional practice. such as reflective writing, classroom observation and feedback sessions and reflection groups, but although these are not outside the scope of our interest here, constraints of length ask for a focus on frameworks and strategies for RP, to what we turn to now.

Frameworks and strategies for reflective practice

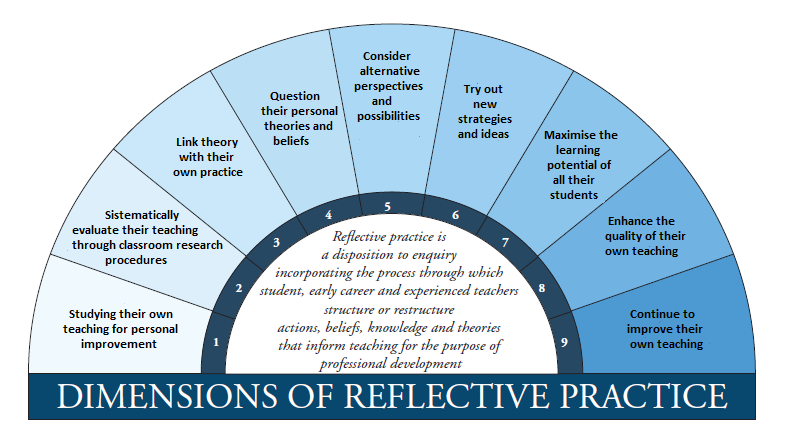

Zwozdiak-Myers’s Framework of Reflective Practice

Designed to guide and structure evidence of reflection in self-study for teacher’s professional development, this framework is meant to capture nine interrelated dimensions, within which three types of discourse can be captured: descriptive, comparative and critical reflective conversations. This framework is based on Jay and Johnson’s (2002) typology of RP and it is underpinned by varied concepts and theories, such as Schön’s (1987) reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action and Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning. Other influences include Moon (1999), for her ideas of development from surface to deep to transformative learning, Baxter Magolda (1999), with stages of epistemological cognition and King and Kitchener (1994), with stages of reflective reasoning. Figure 3.2, below, represents the nine dimensions within Zwozdiak-Myers’s framework:

Figure 1: Zwozdiak-Myers’s Framework of Reflective Practice (2012, p. 5)

These nine dimensions do not necessarily occur in a linear way, as there can be overlaps, or alternated ways in which they can occur in practice. The framework suits different levels of experience, rather than representing a progressive way of “becoming reflective”. In simple terms: “dimensions” are not to be confused with “stages”. Three types of discourse (descriptive, comparative and critical) can be captured from these nine dimensions. This would be applicable, for example, to analyse reflections deriving from blogs, reflective journals, recorded interviews on teaching practice, feedback sessions, etc., to make sense of the way participants construct their thoughts, or consider the need for change, on the basis of their awareness.

In order to uncover descriptive dimensions of reflection, the framework could be used by teachers (or a researcher) to respond to questions such as: “What was taught? How was it taught? Did pupils achieve the intended learning outcomes? What teaching strategies were effective, or ineffective? How do I know? What does this mean? How does this make me feel? How might I do things differently next time?” (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 25).

Comparative reflections would require answers to questions such as: “What alternative strategies might I use in my teaching? (…) What research enables me to gain further insights into this matter? In what ways can I improve the ineffective aspects of my practice? (…)” (ibid). These questions might serve as a springboard to further subsequent elaborations.

In order to uncover critical reflection, professionals would be asking questions such as:

Why select this particular strategy for this particular group of pupils on this particular occasion within this particular context rather than an alternative? What criteria can support my decision-making? How does my choice of objectives, learning outcomes, teaching and assessment strategies reflect the cultural, ethical, ideological, moral, political and social purposes of schooling? (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 27)

The above questions are only some examples of issues that might arise during an RP process. The point is to be able to capture the dimensions of refection, in order to make better profit of personal experiences and to be able to explore “vulnerabilities, conflicts, choices and values’ and take measure of the ‘uncertainties, mixed emotions, and multiple layers (…) of their experience” (Zwozdiak-Myers, 2012, p. 33).

Farrell’s Framework for Reflecting on Practice

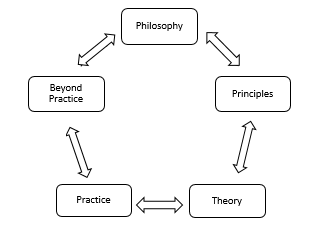

The Framework for Reflecting on Practice (Farrell, 2015) was adapted from the author’s earlier framework (Farrell, 2004), in order to be suitable for teaches at all levels of development. The new framework revisits Dewey (1933), the “loop learning” (Argyris; Schön, 1974), and Schön (1983), and also has the influence of Shapiro and Reiff’s (1993) model of reflective inquiry on practice (RIP), from the field of psychology. Farrell’s (2015) model is an evidence based approach that “includes the person who is reflecting”, as it is “an overall framework for teachers to reflect on their philosophy, beliefs, values, theories, principles, classroom practices, and beyond the classroom” (p. 20). Figure 2 illustrates his framework:

Figure 2: Farrell’s (2015) Framework for Reflecting on Practice

The author explains that the five stages/levels of RP, as illustrated in Figure 2, are not isolated (hence the two-way arrows), but they can be explored on their own, or in conjunction with others, according to the teacher’s needs or preferences. The framework allows for flexibility. Moreover, it was designed for either a deductive or an inductive approach, and can be used by teachers alone, in pairs or in groups. The five stages/levels in the framework can be summarised as follows:

Philosophy: Accessing philosophy, “a window to the roots of a teacher’s practice” (p. 24) consists of obtaining self-knowledge by exploring the background behind personal values. This involves contemplation and more active evidence based RP, such as reflective writing, which allows the understanding of values, ethics and assumptions that underlie a person’s practice.

Principles: Accessing principles requires opportunities for articulation, so that teachers examine and question their assumptions, beliefs and conceptions, and how they translate (or not) into classroom practice. For example, teachers can examine images, metaphors and maxims of teaching and learning.

Theory: Teachers consider aspects of lesson planning (forward, central and backward planning), such as content, techniques, activities, routines and goals. Also, teachers may examine critical incidents, or carry out case studies.

Practice: Accessing practice, “10 percent of the whole iceberg” (p. 29), involves reflection on the more tangible part of teaching. It begins with examination of observable actions and students’ reactions during lessons. This can take the form of reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action and reflection-for-action. Several methods can be used for accessing practice, such as self or peer classroom observation, peer critical friendship, group observations, lesson recording, or action research.

Beyond practice: This takes on a socio-cultural dimension, with critical reflection, involving moral, political and social issues that impact a teacher’s practice. This enables understanding of the foundational theories (philosophy, principles, theory) and allows for contributing to the betterment of society at large. A suggestion for accessing critical reflection is the use of teacher’s reflection groups.

Farrell’s (2015) Framework for Reflection on Practice aids the comprehension of processes of awareness-raising, particularly because of the idea of the overlaps of stages/levels of reflection.

Edge’s framework of cooperative development

Non-judgmental communication is the central idea supporting Edge’s framework of cooperative development (Edge, 1992; 2002; Edge; Attia, 2014), which is an inquiry-based approach placing self-development at the heart of professional development. The author explains that “The approach is not about a way of teaching but, rather, a way of being a teacher” (Edge; Attia, 2014, p. 65). Edge’s framework derives from the humanistic approaches to psychology, most specifically from Rogers’s (1992) fundamental proposition, which is that “the main barrier to mutual interpersonal communication is our very natural tendency to judge, to evaluate, to approve or disapprove the statement of the other person, or the other group” (Rogers, 1992, p. 28).

The principle behind Edge’s framework is that we learn from three main ways: through our intellect, through our experience and through articulation. Cooperative development is considered by the author as a way through which this third form of learning (articulation) can be successfully achieved: “We learn by speaking, by working to put our own thoughts together so that someone else can understand them” (Edge, 2002, p. 19). The way this framework is put into practice involves taking up roles that deviate from a normal type of conversation, as follows: Participants carry out the roles of “speaker” and “understander”, agreeing to a way of interaction that aims to get closer to the concept of “conversation” rather than “discussion” because discussions imply a competitive element. This framework is suggested as “a deliberately different way of behaving, of speaking, and of listening (…) different from our usual ways of interacting” (p. 21). The author explains that while trying to put thoughts into a coherent shape, one becomes aware of the need to develop or reshape ideas. This brings together intellectual and experiential knowledge, fusing the two through articulation.

Within Edge’s framework, there are five interactive techniques, adapted from The Skilled Helper (Egan, 1982):

Attending: This refers to listening supportively and communicating interest (for example, including signals of listenership, such as response tokens or with body language);

Reflecting: this is used in the sense of reflecting like a mirror, as the understander empathetically mirrors the speaker’s ideas, to bring them to the speaker’s awareness, similar to the role of a counsellor. This serves the purpose of checking understanding, which, if not achieved, requires reformulation from the speaker;

Making connections: the understander draws links from within the speaker’s discourse, making every effort to understand him/her, “helping the Speaker develop the Speaker’s own ideas as the Speaker clarifies them and discovers where they lead” (Edge, 1992, p. 62);

Focusing: The understander facilitates the speaker’s articulation by questioning and requiring clarity;

Into action: The understander follows what the speaker decides, as a result of the speaker’s own reformulations.

Throughout this process, the understander must follow three underlying principles: respect, empathy and sincerity. Basically, respect refers to accepting evaluations, opinions and intentions without judging these according to the understander’s values, but rather attempting to understand the way the speaker articulates them. In this way, acceptance is different from agreement. Empathy refers to trying to “see things according to the speaker’s frames of reference” (Edge, 2002, p. 28), asking for “more and more clarification”, so that the understander can apprehend the speaker’s perceptions as fully as possible. Sincerity refers to being genuine about respect and empathy. Without these three underlying principles, the author categorically affirms that CD is impossible.

By following the cooperative development framework, the speaker has the chance to increase self-awareness with the help of the understander, through discoveries that “might otherwise not be made in the cut and thrust of argument” (Edge 2002. p. 32). These are the individual gains enabled by cooperative work with colleagues, according to Edge (2012, p. 13):

• awareness of your own strengths and skills;

• appreciation of the strengths and skills of others;

• willingness to listen carefully to others;

• ability to interact positively with changes in your teaching environment;

• capacity to identify directions for your own continuing development;

• potential to facilitate the self-development of others.

Edge forewarns, after having had experience implementing co-operative development inside multinational companies in the USA, and among teachers in Poland, Pakistan, and Brazil that “Co-operative Development is not for everyone: its style does not suit some people and, anyway, it would be naive to expect massive take-up of the extra effort involved” (Edge, 1992, p. 70). This framework can be applied to shed some light on conversation and discourse analysis, in terms of allowing observance of the supportive aspects of interactions, for example, it is applicable to the analysis of peer observation feedback or group discussions.

Conclusion

Despite differing on focus and strategies applicable to each, the three frameworks herein discussed involve rationality and consciousness, with an aim at the refinement of professional development. Also, the three of them carefully consider the importance attributed to length of experience in professional development. This is of great importance, as we are not only considering procedures or ways of engaging in RP, but also ways of analysing its outcomes.

Especially if we are studying these three frameworks as applied to analysis of outcomes (one individual analysing his/her outcomes from an RP process) it would be advisable to have in mind the need to prepare teachers to engage in experimenting with these frameworks. The reason why I say this is because previous research of mine has attested that engaging in reflection might bring up knowledge (or recognition) of positive and not very positive aspects of one’s practice and, most importantly, of one’s personal characteristics, because there can be pedagogical and personal implications along the process. Anyone who engages in RP will inevitably face some level of discomfort, perhaps fear, perhaps anger or other sorts of psychological and social struggles. In this aspect, perhaps the one framework that overtly prescribes some sort of previous preparation, as well as offering guidelines for engagement is Edge’s framework (with guidelines to act as a speaker and as an understander).

Both Zwozdiak-Myers’s and Farrell’s framework provide a lens and pedagogical tool, through and within which student, early career and experienced teachers can both demonstrate and capture evidence of effective reflective practice, however these authors are, perhaps, mostly centered on content for reflection and on individual self-understanding, whereas Edge focusses on allowing the participants to help each other in the process of making sense of their experience.

Still, I believe that anyone who engages in any of these RP frameworks, will eventually analogically apply their understanding to their practice, sooner or later. Whatever framework applied to reflect or to study one’s reflections require willingness to accept problems and embrace the need to change or to try new things.

Vera Lucia Lima Carvalho - Doutora em TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) pela University of Limerick, na Irlanda; Especialista em Programação de Ensino da Língua Inglesa, pela Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE); Graduada com licenciatura plena em Letras, com habilitação para línguas inglesa e portuguesa pela Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE). Atua como professora pesquisadora na Universidade do Estado da Bahia – UNEB E-mail: veralucialimacarvalho@gmail.com

- ARGYRIS, C.; SCHÖN, D. A. Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.1974.

- BROOKFIELD, S. Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass, 1995.

- BROOKFIELD, S. D. The skillful teacher: On technique, trust, and responsiveness in the classroom. John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- CALDERHEAD, J.; GATES, P. Conceptualising reflection in teacher development. London: Routledge, 2004.

- CANAGARAJAH, A. S. Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: University Press Oxford, 1999.

- CRYSTAL, D. English as a global language. UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- CRYSTAL, D. English as a global language. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. v. Book, Whole.

- CRYSTAL, D. English as a global language. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- DAY, C. Developing teachers: the challenges of lifelong learning. Philadelphia, Pa; London: Falmer Press, 1999. v. Book, Whole).

- DEWEY, J. How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educational process. Lexington, MA: Heath, 1933.

- EDGE, J. Co-operative development. In.: ELT journal, 46, n. 1, p. 62-70, 1992.

- EDGE, J. Action Research. Case Studies in TESOL Practice Series. ERIC, 2001.

- EDGE, J. Continuing cooperative development: a discourse framework for individuals as colleagues. Great Britain; Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002. v. Book, Whole.

- EDGE, J.; ATTIA, M. Cooperative development: a non-judgmental approach to individual development and increased collegiality. In.: Actas De Las Vi Y Vii Jornadas Didácticas Del Instituto Cervantes De Mánchester, p. 65-73, 2014.

- EGAN, G. The skilled helper. Cengage Learning, 1982.

- ERAUT, M. Developing professional knowledge and competence. Washington, D.C; London: Falmer Press, 1994. v. Book, Whole.

- ERAUT, M. Developing professional knowledge and competence. London: Routledge, 2002.

- FARR, F.; MURPHY, B.; O'KEEFFE, A. The Limerick corpus of Irish English: Design, description and application. In.: Teanga: The Irish Yearbook of Applied Linguistics, n. 21, p. 5-29, 2004.

- FARRELL, T. S. Reflective practice in action: 80 reflection breaks for busy teachers. Pennsylvania: Corwin Press, 2004.

- FARRELL, T. S. Reflecting on reflective practice:(re) visiting Dewey and Schön. TESOL Journal, 3, n. 1, p. 7-16, 2012.

- FARRELL, T. S. Promoting teacher reflection in second language education: A framework for TESOL professionals. London: Routledge, 2015.

- FREEMAN, D. Language, sociocultural theory, and L2 teacher education: Examining the technology of subject matter and the architecture of instruction. Language learning and teacher education: A sociocultural approach. p. 169-197, 2004.

- FREIRE, P. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.

- HEDGE, T. Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- HOLLIDAY, A. The Struggle to teach English as an International Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. (Oxford Applied Linguistics).

- JAY, J. K.; JOHNSON, K. L. Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, n. 1, p. 73-85, 2002.

- KACHRU, B. B. Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: the English language in the outer circle. In: BOLTON, K. e KACHRU, B. B. (Ed.). World Englishes: critical concepts in linguistics. London and New York: Routledge, 1985. v. 3, p. 241-255.

- KING, P. M.; KITCHENER, K. S. Developing reflective judgment: Understanding and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1994. (Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series and Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series.

- LAVE, J.; WENGER, E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- MAGOLDA, M. B. B.; KING, P. M. Toward reflective conversations: an advising approach that promotes self-authorship. Peer Review, 10, n. 1, p. 8, 2008.

- MOON, J. A. Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice. Psychology Press, 1999.

- MOON, J. A. Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. London: Routledge, 2013.

- PENNYCOOK, A. Markets, flows, fixities and peripheries. In: Sociolinguistics of Globalization Conference, 2015, University of Hong Kong.

- PHILLIPSON, R. Linguistic imperialism continued. Routledge, 2009.

- ROGERS, C. Communication: Its blocking and its facilitation. In: TEICH, N. (Ed.). Rogerian Perspectives: Collaborative Rhetoric for Oral and Written Communication. Northwood, NJ: Ablex, 1992.

- SCHÖN, D. A. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic books, 1983.

- SHAPIRO, S. B.; REIFF, J. A framework for reflective inquiry on practice: Beyond intuition and experience. Psychological Reports, 73, n. 3 suppl, p. 1379-1394, 1993.

- VALLI, L. Reflective teacher education: Cases and critiques. Suny Press, 1992.

- VAN MANEN, M. Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical. Curriculum inquiry, 6, n. 3, p. 205-228, 1977.

- WENGER, E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- ZWOZDIAK-MYERS, P. The Teacher's Reflective Practice Handbook: Becoming an Extended Professional Through Capturing Evidence-informed Practice. Routledge, 2012.

Recebido em: 21-set-2023

Aceito em: 11-jun-2024

Todo o conteúdo deste trabalho é publicado sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.